|

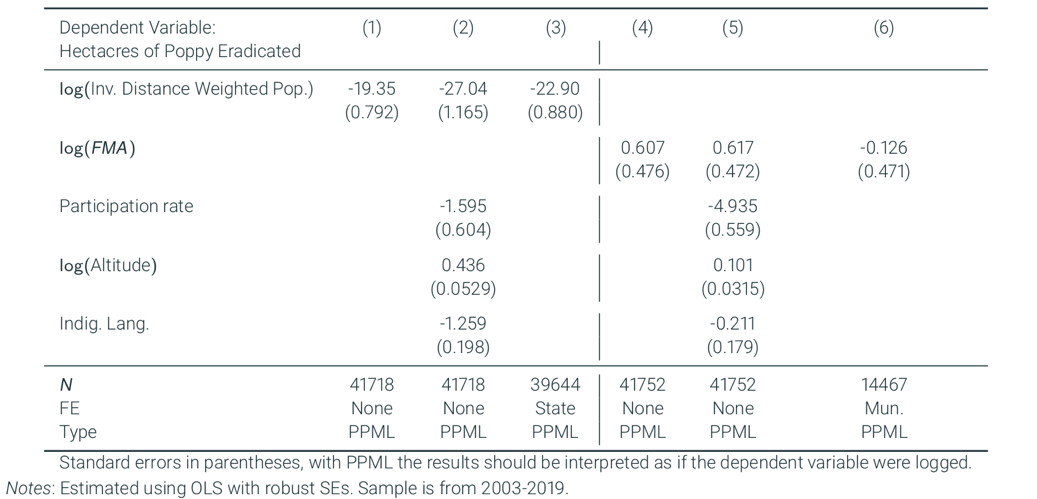

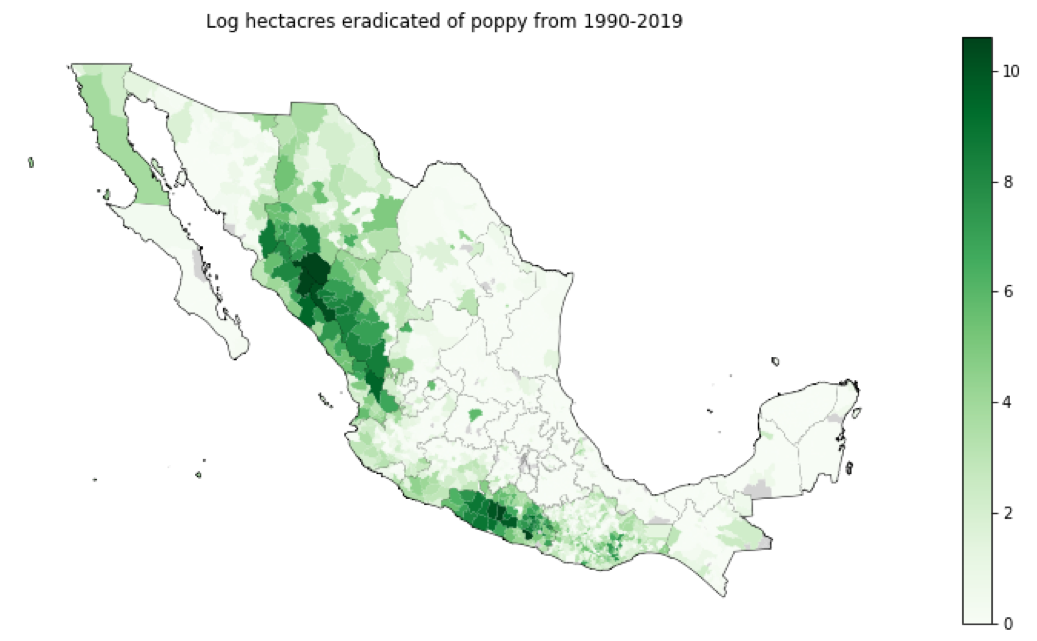

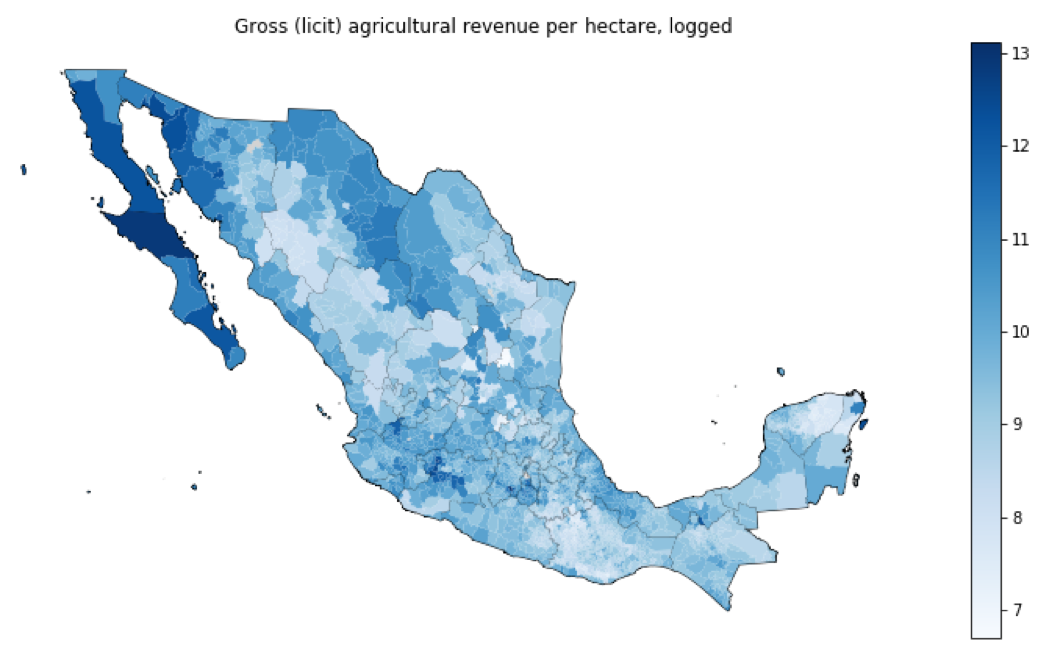

By: Jay Sayre Strategies to reduce the production of illegal drugs have changed remarkably little at the top of the supply chain in the last several decades, consisting mostly of heavy handed enforcement efforts as part of the war on drugs. While supporters of this approach have justified these methods on the basis of the consequences of illegal drugs (such as the human costs of addiction), much more work is required to understand the economic forces driving illicit crop production and which alternative strategies may (or may not) be effective. Part of this conversation needs to involve a critical analysis of the role the military and police have historically played in stemming the production of drugs, a topic that parallels the recent conversations in the United States surrounding the adverse effects of policing on Brown and Black communities. Related to this discussion, there is an opportunity to examine whether there are viable alternatives available that can still reduce drug production while minimizing some of the harmful outcomes of heavy-handed enforcement. Administrations in countries such as Colombia, Mexico, and Peru have begun to consider alternative programs designed to curb the production and smuggling of illegal drug crops. Part of what has driven this has been an increased recognition from policymakers of the harms of eradication efforts. These harms include the health risks of chemicals used to eradicate drugs as well as the threat of state-administered violence in drug producing communities. In my work, I focus on the context of Mexico, where marijuana and opium poppy are widely produced, and from an American perspective, is the largest exporter of opium poppy to the United States (according to the DEA, around 90 percent of locally consumed heroin is imported from Mexico). According to information provided by the Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA), the Mexican military destroyed 365,062 hectares of opium poppy and 333,546 hectares of marijuana between January 2000 and May 2020. During the same period, about 13 percent of the total eradications of opium poppy and a similar percentage for marijuana were conducted through aerial fumigation campaigns. During these campaigns, low flying aircraft spray chemicals known to be carcinogenic to destroy illicit drug crops, with the remainder eradicated by hand through cutting and burning the crops. Despite current Mexican President López Obrador’s calls for a softer approach to drug policy, best exemplified by his campaign slogan, abrazos no balazos (hugs not bullets), I calculate that the rate of aerial fumigation has increased on average during López Obrador’s administration to 19.5 percent, from an average of 12.64 percent during the administration of former President Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018). Another important harm of eradication efforts may be the loss of income for the rural farmers that cultivate such crops. A recent study examining communities in Mexico that produce opium poppy[1] suggests that illicit crop production (and the income it provides) is deeply integrated into society in these places -- “between 70% and 95% of the population – men, women, and children – work in, or earn their living through, activities directly or indirectly related to opium” (Noria Research). Although there are considerable differences in the composition of each of these communities in Mexico, some are composed primarily by indigenous residents, where it is hypothesized that the “income generated by commercializing opium has helped reduce the expulsion of laborers from indigenous communities in search of employment [elsewhere in Mexico], and contributed to lowering rates of migration to the United States” (Morris, 2021). In recognition of the harms of eradication programs, numerous politicians have proposed policies to target the twin aims of improving the welfare of drug crop farmers and reducing their production. Last month, President López Obrador announced an initiative to study alternative approaches to drug policy, such as the commercialization of marijuana and opium poppy. It remains unclear whether the legal market for opium poppy is large enough to provide any meaningful source of demand for these products. Domestic demand for legal products derived from opium poppy such as morphine is around 700 kilograms, which could be produced with only 321 hectares of land, which is far less than the average amount of poppy eradicated in a couple of weeks in a given growing season for the most prominent poppy producing municipalities (Grandmaison et al., 2019). Other ideas that López Obrador and others have proposed include subsidies to the price of legal crops, most frequently maize, in areas where drug crops have historically been grown. The ex-defense chief recently handed over by American authorities and cleared of corruption charges by Mexico, Salvador Cienfuegos, has proposed a price floor of 3,500 pesos per ton of maize, roughly double the price of maize in rural regions, and other governors of states have proposed even larger subsidies of up to 15,000 pesos per ton to discourage the production of drug crops. Given the relatively scant history of successful crop substitution programs (Colombia’s recent program has been plagued by implementation issues), in my work I aim to provide ex-ante policy analysis of the effectiveness of these potential programs as a possible alternative to current eradication campaigns. I also seek to identify the size of the subsidies necessary to achieve the simultaneous policy objectives of reducing illegal crop production and increasing incomes of the rural farmers involved with production. To do so, I start by examining the economic factors which may lead farmers to produce drugs. The common wisdom is that illicit crop production tends to occur in remote areas with poor market access where only immensely profitable drug crops can overcome potentially highly trade barriers. I investigate this thinking empirically and find that a 1 percent increase in “remoteness”, or a decrease in the inverse distance weighted sum of populations elsewhere relative to a municipality, tends to increase the amount of yearly eradications of poppy in a given municipality by roughly 20-25 percent. However, I also find that a standard market access measure (as in Redding and Venables 2003), which captures both distances to large centers of demand for agricultural goods as well as the relative price index of those locations, is not significantly associated with differences in the eradication of opium poppy. Perhaps this may be explained by the unique geography of opium poppy production in Mexico, which tends to occur in the highlands of the Sierras that straddle Mexico’s coastlines, which oftentimes places these poppy producing municipalities in the nearby vicinity of regions of high value agricultural regions, even though those drug crop producing regions tend to have a much rougher geography that is not as conducive to agricultural production. One of the most striking predictors of illicit crop production tends to be the gross revenue coming from legal crops per hectare (I plot the average between 2011 and 2019 below), where municipalities that tend to produce drugs exhibit much lower average revenues per unit of land. One explanation for this visual correlation may be that in these municipalities, unreported illicit crop production accounts for a large share of total agricultural revenues. Next, I undertake an econometric approach to understand the degree to which farmers shift between growing illicit and licit crops as their prices change. In particular, I examine how the rise of fentanyl in the United States, which caused the farm-gate price of opium poppy to fall almost four-fold between 2017 and 2018, has led farmers to shift into producing alternative crops such as maize or avocados or migrate elsewhere. Using information on the prices of both illicit and licit crops, agricultural information such as crop and production decisions, labor costs, and estimates of poppy production, I estimate my main regression equation, which regresses relative prices of illicit to licit crops on their production shares, instrumenting for the average reduction in farm-gate prices of fentanyl, interacted with the area’s distance to the United States border, where the most of the opium poppy grown in Mexico is destined. Through this procedure, I estimate elasticities of transformation between the production of legal and illegal crops which suggest that the ability of farmers to shift between the two is relatively low. Ultimately, the source of such low abilities to shift between production of licit and illicit crops is likely a result of institutions, corruption, and potentially the prominence of criminal organizations, and the factors driving my quantitative results are worth further investigation. Informed by this statistical evidence, I develop a theoretical model which incorporates many of the features of illicit drug production in Mexico. This model allows me to conduct counterfactual simulations of the effects of a wide range of hypothetical policies on both farmer welfare and total illicit crop production. My model features trade across regions and international borders that can be easily matched to moments found in the data such as land shares dedicated to legal and illegal crops, populations, and observed yields which can be used to derive fundamental agricultural productivities. It is necessary for any realistic model to incorporate the “balloon effects'' drug policy researchers have identified in response to reductions in illegal drug supply driven by government policies, the low elasticities of demand for narcotics imply that prices rise sharply, yielding other regions or countries to produce more. In preliminary findings, I conclude that applying a 10 percent subsidy to maize would reduce opium poppy production in a given municipality on average by approximately 5 percent. However, this reduction in aggregate supply yields a national price increase in opium poppy. Given the increase in poppy prices, I find a smaller number of regions increase their production of poppy by up to 25 percent, limiting the reductions elsewhere. Although my findings are preliminary, my results suggest caution in the belief that subsidy programs will entirely eliminate production of drugs. However, even if such programs reduce poppy production no more than militarized crop eradication programs, are these policies better for the well-being of the country as a whole (including the welfare of the local farmers who depend on such crops) vis-à-vis heavy handed eradication campaigns? Abstracting from the costs of the military in providing drug enforcement, the eradications often remove the main source of income for these rural communities, and many protests against eradications have occurred in such regions. In ongoing work, I intend to explore this question further and provide quantitative comparisons of the potential welfare costs of both approaches, which may be useful to policymakers eyeing such changes. Work Cited Grandmaison, RL, Morris, N and Smith, B. (2019). The Last Harvest? From the US Fentanyl Boom to the Mexican Opium Crisis. Journal of Illicit Economies and Development, 1(3): pp. 312–329. Nathaniel Morris (2021). Opium, Integration and Resistance in the indigenous communities of Nayarit. Noria Research Mexico Opium Project, #6. Noria Research (2021). Why is opium production crucial to better understand the War on Drugs in Mexico? Retrieved from https://noria-research.com/mxac/opium-project/key-insights-opium-project-dossier-n1/ Redding, S., & Venables, A. J. (2003). South-East Asian export performance: external market access and internal supply capacity. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 17(4), 404-431. Source: Author’s calculations using data provided by SEDENA. Source: Author’s calculations using data provided by the Service of Agrofood and Fisheries Information (SIAP, by its initials in Spanish). [1] Defined as communities in which eradications of opium poppy have occurred more than 12 of the last 17 years and subject to a minimum total acreage of eradications by the study authors. Source: Author’s calculations using data provided by SEDENA. Source: Author’s calculations using data provided by the Service of Agrofood and Fisheries Information (SIAP, by its initials in Spanish).

7 Comments

12/20/2022 07:36:11 pm

İnstagram takipçi satın almak istiyorsan tıkla.

Reply

1/8/2023 12:16:59 am

100 tl deneme bonusu veren siteleri öğrenmek istiyorsan tıkla.

Reply

5/22/2023 08:52:18 pm

Thank you for stating that your model includes cross-regional and cross-border trade that is easily matched to data points like populations, observed yields, and land shares allocated to legal and illegal crops that can be used to derive basic agricultural productivities. To grow crops, my mother wants to purchase land. She wants to know if purchasing land in a certain location with the intention of engaging in agricultural production is appropriate and lawful. I'll advise her to enlist the aid of land surveyors.

Reply

6/30/2023 04:27:19 am

En iyi bayburt ilan sitesi burada. https://bayburt.escorthun.com/

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed