|

This summer, BEE is excited to offer a mentoring program for underrepresented minorities who are applying to graduate school in economics or a related field in Fall 2023 or Fall 2024. Current PhD students will be matched with mentees to provide feedback and support on the application process.

Interested in being a mentee? Please fill out this application. Mentees will be accepted on a rolling basis until all mentors are matched or August 4, 2023. Mentors are current PhD students from UC Berkeley's Departments of Economics and Agricultural and Resource Economics, Haas School of Business, and Goldman School of Public Policy. Current Berkeley PhD students interested in being mentors, please fill out this application by July 16, 2023 at 5pm.

0 Comments

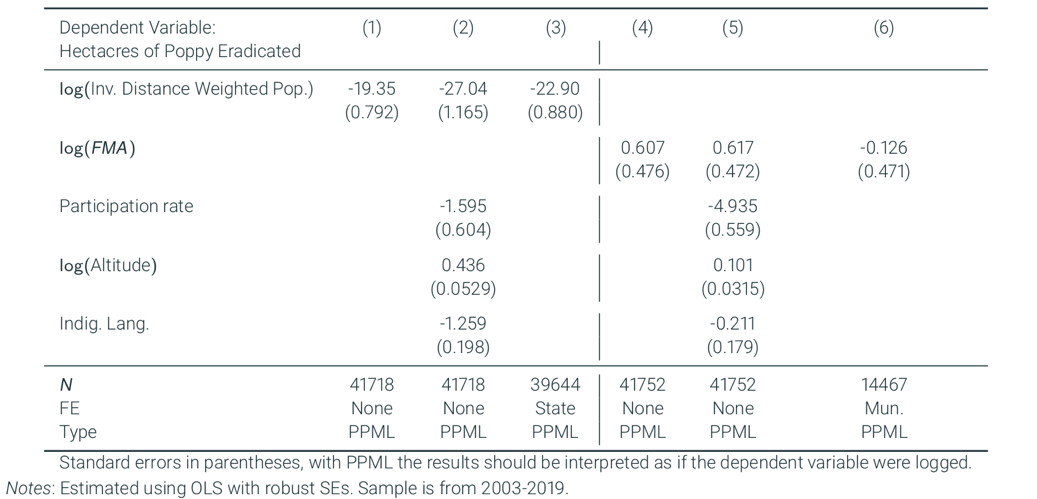

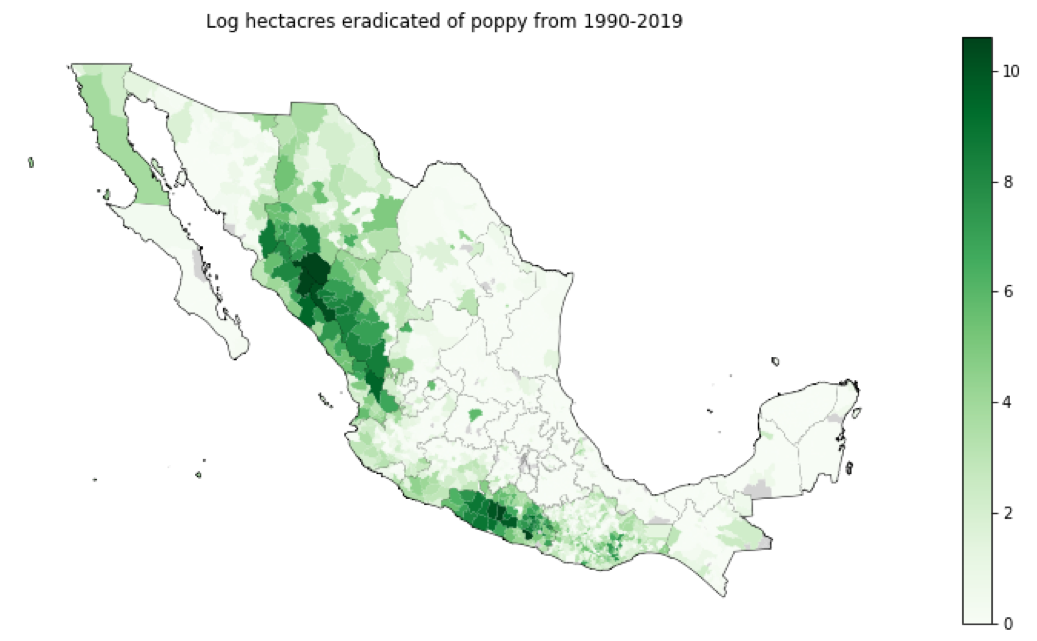

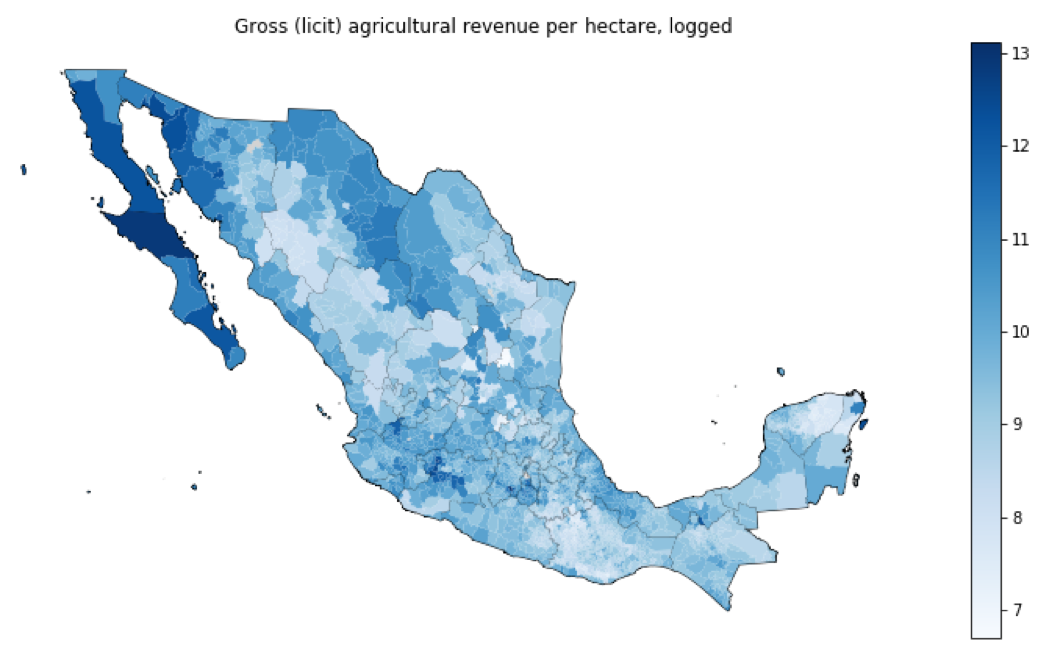

By: Jay Sayre Strategies to reduce the production of illegal drugs have changed remarkably little at the top of the supply chain in the last several decades, consisting mostly of heavy handed enforcement efforts as part of the war on drugs. While supporters of this approach have justified these methods on the basis of the consequences of illegal drugs (such as the human costs of addiction), much more work is required to understand the economic forces driving illicit crop production and which alternative strategies may (or may not) be effective. Part of this conversation needs to involve a critical analysis of the role the military and police have historically played in stemming the production of drugs, a topic that parallels the recent conversations in the United States surrounding the adverse effects of policing on Brown and Black communities. Related to this discussion, there is an opportunity to examine whether there are viable alternatives available that can still reduce drug production while minimizing some of the harmful outcomes of heavy-handed enforcement. Administrations in countries such as Colombia, Mexico, and Peru have begun to consider alternative programs designed to curb the production and smuggling of illegal drug crops. Part of what has driven this has been an increased recognition from policymakers of the harms of eradication efforts. These harms include the health risks of chemicals used to eradicate drugs as well as the threat of state-administered violence in drug producing communities. In my work, I focus on the context of Mexico, where marijuana and opium poppy are widely produced, and from an American perspective, is the largest exporter of opium poppy to the United States (according to the DEA, around 90 percent of locally consumed heroin is imported from Mexico). According to information provided by the Secretariat of National Defense (SEDENA), the Mexican military destroyed 365,062 hectares of opium poppy and 333,546 hectares of marijuana between January 2000 and May 2020. During the same period, about 13 percent of the total eradications of opium poppy and a similar percentage for marijuana were conducted through aerial fumigation campaigns. During these campaigns, low flying aircraft spray chemicals known to be carcinogenic to destroy illicit drug crops, with the remainder eradicated by hand through cutting and burning the crops. Despite current Mexican President López Obrador’s calls for a softer approach to drug policy, best exemplified by his campaign slogan, abrazos no balazos (hugs not bullets), I calculate that the rate of aerial fumigation has increased on average during López Obrador’s administration to 19.5 percent, from an average of 12.64 percent during the administration of former President Enrique Peña Nieto (2012-2018). Another important harm of eradication efforts may be the loss of income for the rural farmers that cultivate such crops. A recent study examining communities in Mexico that produce opium poppy[1] suggests that illicit crop production (and the income it provides) is deeply integrated into society in these places -- “between 70% and 95% of the population – men, women, and children – work in, or earn their living through, activities directly or indirectly related to opium” (Noria Research). Although there are considerable differences in the composition of each of these communities in Mexico, some are composed primarily by indigenous residents, where it is hypothesized that the “income generated by commercializing opium has helped reduce the expulsion of laborers from indigenous communities in search of employment [elsewhere in Mexico], and contributed to lowering rates of migration to the United States” (Morris, 2021). In recognition of the harms of eradication programs, numerous politicians have proposed policies to target the twin aims of improving the welfare of drug crop farmers and reducing their production. Last month, President López Obrador announced an initiative to study alternative approaches to drug policy, such as the commercialization of marijuana and opium poppy. It remains unclear whether the legal market for opium poppy is large enough to provide any meaningful source of demand for these products. Domestic demand for legal products derived from opium poppy such as morphine is around 700 kilograms, which could be produced with only 321 hectares of land, which is far less than the average amount of poppy eradicated in a couple of weeks in a given growing season for the most prominent poppy producing municipalities (Grandmaison et al., 2019). Other ideas that López Obrador and others have proposed include subsidies to the price of legal crops, most frequently maize, in areas where drug crops have historically been grown. The ex-defense chief recently handed over by American authorities and cleared of corruption charges by Mexico, Salvador Cienfuegos, has proposed a price floor of 3,500 pesos per ton of maize, roughly double the price of maize in rural regions, and other governors of states have proposed even larger subsidies of up to 15,000 pesos per ton to discourage the production of drug crops. Given the relatively scant history of successful crop substitution programs (Colombia’s recent program has been plagued by implementation issues), in my work I aim to provide ex-ante policy analysis of the effectiveness of these potential programs as a possible alternative to current eradication campaigns. I also seek to identify the size of the subsidies necessary to achieve the simultaneous policy objectives of reducing illegal crop production and increasing incomes of the rural farmers involved with production. To do so, I start by examining the economic factors which may lead farmers to produce drugs. The common wisdom is that illicit crop production tends to occur in remote areas with poor market access where only immensely profitable drug crops can overcome potentially highly trade barriers. I investigate this thinking empirically and find that a 1 percent increase in “remoteness”, or a decrease in the inverse distance weighted sum of populations elsewhere relative to a municipality, tends to increase the amount of yearly eradications of poppy in a given municipality by roughly 20-25 percent. However, I also find that a standard market access measure (as in Redding and Venables 2003), which captures both distances to large centers of demand for agricultural goods as well as the relative price index of those locations, is not significantly associated with differences in the eradication of opium poppy. Perhaps this may be explained by the unique geography of opium poppy production in Mexico, which tends to occur in the highlands of the Sierras that straddle Mexico’s coastlines, which oftentimes places these poppy producing municipalities in the nearby vicinity of regions of high value agricultural regions, even though those drug crop producing regions tend to have a much rougher geography that is not as conducive to agricultural production. One of the most striking predictors of illicit crop production tends to be the gross revenue coming from legal crops per hectare (I plot the average between 2011 and 2019 below), where municipalities that tend to produce drugs exhibit much lower average revenues per unit of land. One explanation for this visual correlation may be that in these municipalities, unreported illicit crop production accounts for a large share of total agricultural revenues. Next, I undertake an econometric approach to understand the degree to which farmers shift between growing illicit and licit crops as their prices change. In particular, I examine how the rise of fentanyl in the United States, which caused the farm-gate price of opium poppy to fall almost four-fold between 2017 and 2018, has led farmers to shift into producing alternative crops such as maize or avocados or migrate elsewhere. Using information on the prices of both illicit and licit crops, agricultural information such as crop and production decisions, labor costs, and estimates of poppy production, I estimate my main regression equation, which regresses relative prices of illicit to licit crops on their production shares, instrumenting for the average reduction in farm-gate prices of fentanyl, interacted with the area’s distance to the United States border, where the most of the opium poppy grown in Mexico is destined. Through this procedure, I estimate elasticities of transformation between the production of legal and illegal crops which suggest that the ability of farmers to shift between the two is relatively low. Ultimately, the source of such low abilities to shift between production of licit and illicit crops is likely a result of institutions, corruption, and potentially the prominence of criminal organizations, and the factors driving my quantitative results are worth further investigation. Informed by this statistical evidence, I develop a theoretical model which incorporates many of the features of illicit drug production in Mexico. This model allows me to conduct counterfactual simulations of the effects of a wide range of hypothetical policies on both farmer welfare and total illicit crop production. My model features trade across regions and international borders that can be easily matched to moments found in the data such as land shares dedicated to legal and illegal crops, populations, and observed yields which can be used to derive fundamental agricultural productivities. It is necessary for any realistic model to incorporate the “balloon effects'' drug policy researchers have identified in response to reductions in illegal drug supply driven by government policies, the low elasticities of demand for narcotics imply that prices rise sharply, yielding other regions or countries to produce more. In preliminary findings, I conclude that applying a 10 percent subsidy to maize would reduce opium poppy production in a given municipality on average by approximately 5 percent. However, this reduction in aggregate supply yields a national price increase in opium poppy. Given the increase in poppy prices, I find a smaller number of regions increase their production of poppy by up to 25 percent, limiting the reductions elsewhere. Although my findings are preliminary, my results suggest caution in the belief that subsidy programs will entirely eliminate production of drugs. However, even if such programs reduce poppy production no more than militarized crop eradication programs, are these policies better for the well-being of the country as a whole (including the welfare of the local farmers who depend on such crops) vis-à-vis heavy handed eradication campaigns? Abstracting from the costs of the military in providing drug enforcement, the eradications often remove the main source of income for these rural communities, and many protests against eradications have occurred in such regions. In ongoing work, I intend to explore this question further and provide quantitative comparisons of the potential welfare costs of both approaches, which may be useful to policymakers eyeing such changes. Work Cited Grandmaison, RL, Morris, N and Smith, B. (2019). The Last Harvest? From the US Fentanyl Boom to the Mexican Opium Crisis. Journal of Illicit Economies and Development, 1(3): pp. 312–329. Nathaniel Morris (2021). Opium, Integration and Resistance in the indigenous communities of Nayarit. Noria Research Mexico Opium Project, #6. Noria Research (2021). Why is opium production crucial to better understand the War on Drugs in Mexico? Retrieved from https://noria-research.com/mxac/opium-project/key-insights-opium-project-dossier-n1/ Redding, S., & Venables, A. J. (2003). South-East Asian export performance: external market access and internal supply capacity. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 17(4), 404-431. Source: Author’s calculations using data provided by SEDENA. Source: Author’s calculations using data provided by the Service of Agrofood and Fisheries Information (SIAP, by its initials in Spanish). [1] Defined as communities in which eradications of opium poppy have occurred more than 12 of the last 17 years and subject to a minimum total acreage of eradications by the study authors. Source: Author’s calculations using data provided by SEDENA. Source: Author’s calculations using data provided by the Service of Agrofood and Fisheries Information (SIAP, by its initials in Spanish).

The Pink Tax: Gender Inequalities in Consumption

By: K. Barnes and J. Brounstein Tl;dr: The “Pink Tax” refers to the hypothesized price premium on women's consumer goods relative to those of men. We advance the first study to rigorously substantiate the existence of the Pink Tax, documenting its magnitude and decomposing the pink tax into its constituent supply and demand components. We find that women pay 4.85% more per unit for goods in the same market than do men. We apply a CES-demand framework to document that women are robustly more-price elastic than are men, indicating that the Pink Tax is not sustained by markups, but through differences in marginal costs of goods consumed, with women purchasing more expensive goods. We also demonstrate that women's consumer goods markets feature a wider variety of UPCs than those of men, suggesting greater competitiveness within women's consumer goods market, further precluding markup channels in generating the observed Pink Tax. The Department of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley has awarded Economists for Equity at Berkeley a grant in the amount of $15,000 to support the student-led organization’s projects and activities.

This award will be instrumental to BEE’s work on understanding gender and racial disparities in the Economics discipline, supporting women and BIPOC graduate students, and increasing diversity of faculty hires. It will also allow BEE to guarantee funding for initiatives like the High School Outreach and Mentorship Program and the Undergraduate Tutoring Program for at least the next two years, allowing us to build a solid foundation for our new initiatives. A big thank you to the Economics Department for supporting our work! For the first time ever this semester, BEE hosted a small grant competition where PhD students in economics-related programs at UC Berkeley (Economics, Agricultural and Resource Economics, Haas, Public Policy, and Health Policy) were invited to apply for the first (ever) Small Research Grants Initiative towards research pertaining to issues of diversity and social justice. We are pleased to announce our first round of grant recipients, selected by an impartial panel of reviewers who are all experts in social justice and diversity-related issues. James Sayre - research on opium poppy markets in Mexico "I study the economic forces that lead rural farmers in Mexico to produce opium poppy, and the feasibility of crop substitution programs to provide a legal alternative to such activities. I measure the degree to which farmers can substitute between legal and illegal crops, and whether out-migration of such regions has also been a way to mitigate changes in the price of illegal crops." Kayleigh Barnes and Jakob Brounstein - research on the "pink tax" "We evaluate the existence of a "pink tax" placed on women's consumer goods and find that women pay higher prices per unit than do men for similar goods. This work can inform whether there exist real consumption inequalities between men and women.” Congratulations James, Kayleigh, and Jakob! We eagerly await the results of your research!

BEE's small grants on Diversity and Social Justice ResearchPhD students in economics-related programs at UC Berkeley (Economics, Agricultural and Resource Economics, Haas, Public Policy, and Health Policy) are invited to apply for the first (ever) Small Research Grants Initiative towards research pertaining to issues of diversity and social justice. What type of work will be considered?Any type of economics research that is related to issues of diversity and social justice. Some relevant topic areas may include crime and policing, diversity in education, environmental justice, economic history, gender and sexuality, geography, health, housing, wealth/income inequality, law and institutions, migration, race, labor markets, and tax policy. Other topics addressing related research questions are encouraged; feel free to apply if you can justify why your research applies to social justice issues. How can the grant money be used?The grant money can be used to cover research expenses of any type (including a stipend for your time). Grants will be awarded as a block stipend. The only requirement for grant recipients is to write a short (1,500-2,000) word blog post about their research that will be published in BEE's website by a pre-determined deadline. How can I apply?There is a short application form that has been emailed to BEE listserv members. It asks for a brief description of your research (approximately 1,000 words total). Please fill out this application before the deadline of Friday, September 11, 2020. If you haven't received the application for any reason but are eligible and interested in the application, please get in touch with us here. How will decisions be made and when will they be reported?A team of experts in social justice/diversity issues will review each application, and consider each project's relevance/contribution to current work in the topic area. We will do our best to match application to reviewers in an appropriate topic area. At least one economist will be a reviewer for each application, yet scholars from other disciplines will also be serving as reviewers. Scores will be averaged across reviewers, and those with the highest scores will be awarded grants. In the event that the number of top scoring applications exceeds the number of available grants, awards will be randomly allocated among top-scorers. We aim to release decisions by around October 11, 2020, but this is a new program so please be patient and flexible. Questions?Email the BEE leadership team members or get in touch with us here.

This fall, BEE is starting a tutoring program that will match graduate students from the Economics department, Agricultural and Research Economics, Goldman School of Public Policy and Haas with undergraduate students of color in the economics major for one on one tutoring. This program has started as an initiative from the Students of Color in Economics (SoCE) association in Berkeley with collaboration of BEE.

Please get in touch with the Tutoring team HERE for more information on how to participate. ''If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.'' - Aboriginal activists group, Queensland, 1970s The events over March to June 2020 have made it abundantly clear that we, the student-led organization formerly Women in Economics at Berkeley, are overdue in expanding our group’s mission to include advocacy and support for all marginalized and underrepresented groups in economics. Starting now, our organization will take an explicit and clear stance in supporting all individuals who identify as part of any structurally under-resourced or under-represented group. To do this, we will need to not only provide loving support but will also need to transform the economics profession to eradicate deep seeds of racism, sexism, homophobia, and cis-sexism that shape our research, teaching, and policy engagement. With this change, we will update our mission statement and the name of the organization to Berkeley Economists for Equity (BEE). We know that we cannot do this alone. It will take community and solidarity across a number of students and institutions to enact change. Everyone must join in this effort - we welcome all who want to work, learn, and grow. In particular, we welcome those who can and will challenge us to be better, to show us how we ourselves are contributing to the perpetuation of injustice. We all have much to learn and are committed to evolving as we identify new ways in which we can move economics towards a more equitable and inclusive environment. Establishing equity is not only the right thing to do, but is absolutely necessary for making the research, pedagogy, and policy that we produce more impactful for creating a brighter world.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed