|

The Pink Tax: Gender Inequalities in Consumption By: K. Barnes and J. Brounstein Tl;dr: The “Pink Tax” refers to the hypothesized price premium on women's consumer goods relative to those of men. We advance the first study to rigorously substantiate the existence of the Pink Tax, documenting its magnitude and decomposing the pink tax into its constituent supply and demand components. We find that women pay 4.85% more per unit for goods in the same market than do men. We apply a CES-demand framework to document that women are robustly more-price elastic than are men, indicating that the Pink Tax is not sustained by markups, but through differences in marginal costs of goods consumed, with women purchasing more expensive goods. We also demonstrate that women's consumer goods markets feature a wider variety of UPCs than those of men, suggesting greater competitiveness within women's consumer goods market, further precluding markup channels in generating the observed Pink Tax. Do women pay more than do men for similar goods? The notion that there exists a price premium on women's consumer goods relative to those of men is colloquially referred to as the “Pink Tax”. This concept has received considerable attention in popular media and recent discourse. (NYC DCA, 2015) The implications of the Pink Tax are wide-reaching: taking into account differences in the cost of consumption prompts us to reframe the widely-studied difference in wages between men and women as a nominal wage gap. As a simple example, estimates of the raw gender pay gap tend to around 20% today, decreasing to about 10% after including differences in qualifications (Blau and Kahn, 2017). The presence of an aggregate Pink Tax on women's consumption, as our findings indicate, augments these consumption inequalities by between 20-40%. However, in spite of its importance as a potential component of gender inequality, the Pink Tax has yet to be rigorously substantiated. Previous work has strived to document the Pink Tax, but there are important methodological decisions that limit the reliability and generality of their findings. In particular, nearly the entirety of such work has tasked itself with documenting the Pink Tax via selected photographs and hand-matched pairs of products: the use of these techniques run the risk of biased selection as well as imprecision. Moreover, while these works do document price-differences, they remain entirely secular as to why such differences exist. We address these gaps by performing a deep-dive into the Pink Tax: 1) whether there does in fact exist a difference in prices paid by men and women for their consumer goods, 2) the magnitude of the difference, and 3) to what extent we can attribute such differences to differences in markups/demand characteristics and differences in supply-side characteristics. But what exactly is the Pink Tax? The majority of popular work on the Pink Tax makes their case by displaying pictures of two presumably similar products---typically one in blue marketed for boys/men and one in pink marketed for girls/women---seemingly inevitably featuring a considerably larger price for the “pink” product. This is the concept we have in mind as we study the pink tax. However, there remains substantial ambiguity as to more precisely what the Pink tax refers to within an astoundingly gray area featuring differences in prices paid for same, similar, and completely different goods that require careful distinction. Moreover, these different cases each have different implications for how we should think about gender inequalities in consumption. Because popular discourse tends to suffer from conflating these different notions, we find it of the utmost importance to draw some distinctions in how we talk about the Pink Tax. Namely, we identify three broad hypothetical cases that result in an observed inequality in the price of consumption by gender: 1) Different prices for goods with the identical inputs: i.e. without changing anything else, by coloring a product pink, retailers and producers can charge a higher price. In a simple supply-and-demand framework, if women are less price-responsive in their purchase decisions than are men, producers would place a price-premium on their goods as a form of price discrimination. The following image shows a scenario that approaches this case; the razor blades are made by the same brand, marketed under the same name and contain the same blades and attributes. 2) Different prices for goods with identical uses but non-identical inputs: i.e. the price difference between goods purchased by men or women is attributable to differences in the cost of production. The lotion example presented below shows how this case deviates from the first, while both products have the same general use, the inputs are likely different. 3) Goods that are exclusively purchased by a single gender. Makeup is a good example of this case: while makeup is not exclusively purchased by women, societal attitudes towards makeup generally categorize makeup as a women’s product that therefore represents an expenditure unaccounted for in men’s consumption. Of course, in reality, any given set of gendered products exhibiting a price-gap likely draws upon a combination of the first two cases. Nonetheless, these distinctions are crucial because they tell meaningfully different stories about the Pink Tax. Beyond rigorously documenting the existence and magnitude of a difference in prices faced by men and women, our work informs to what extent the difference is driven by:

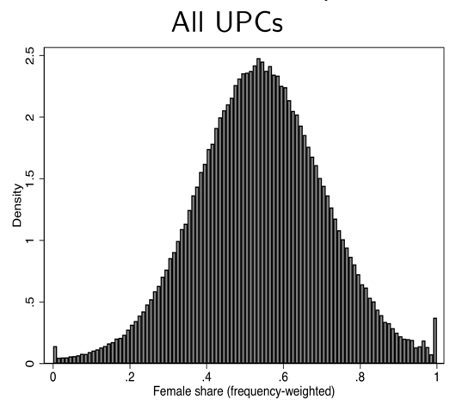

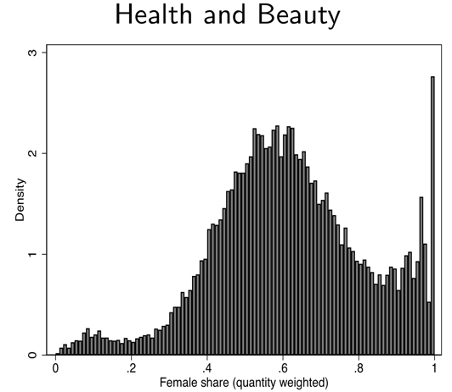

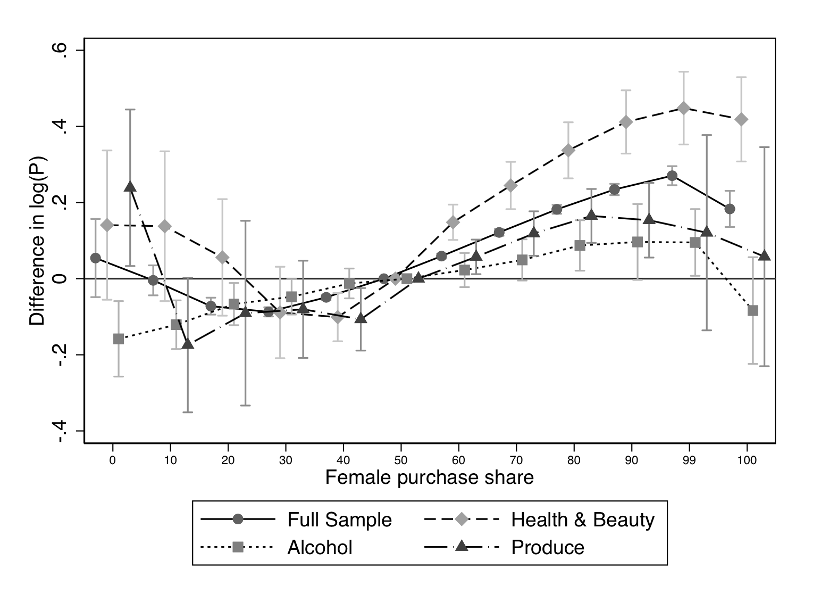

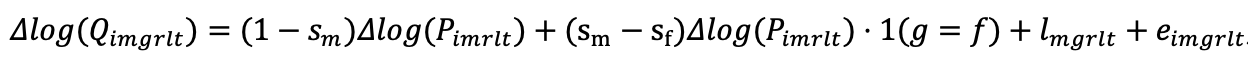

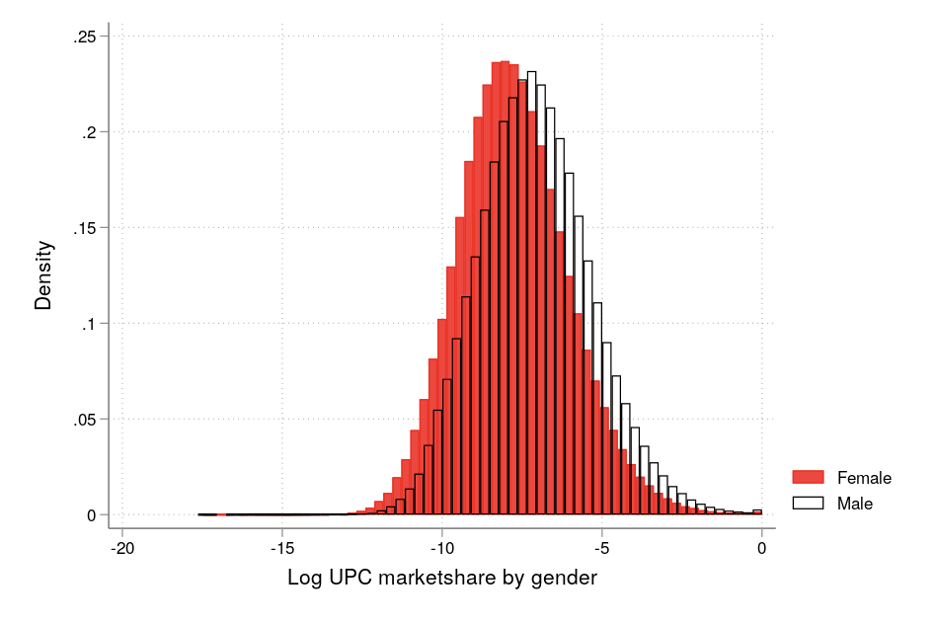

Studying the Pink Tax To measure and decompose the Pink Tax, we compile data from several sources, run descriptive analyses and estimate price elasticities with a CES demand model. The Nielsen Consumer Panel Survey features a 15-year rotating panel of households and the near-universe of their purchases at standard US retailers and grocery stores. Importantly, the data includes rich demographic information on the individual side as well as highly detailed product and purchase characteristics---including deal/sale usage, prices paid/quantities consumed, and a granular decomposition of products into tractable market-hierarchies by level of specificity. We augment this data with Nielsen Retailer Scanner data for more comprehensive information on the consumption of individual UPCs (however, not tied to consumer identifiers) and Promodata (from PRICE-TRAK via Globus) data on select manufacturing/supplier prices to retailers. Descriptive Evidence: Women’s products are more expensive We begin our analysis by documenting differences in prices paid by men and women for their consumer goods, identifying products that are highly gendered in terms of who consumes them and documenting price differences between these gendered and ungendered products. We compare prices paid for goods in the same product market across men and women and find that women on average consume products priced 4.85% higher than comparable products bought by men after controlling for demographic observables. We test for differences in price shopping behavior between men and women by comparing prices paid for the same exact product (UPC) and find that women acutely exhibit more price shopping, paying 0.66% less than men do. Next, we turn our attention to the products themselves rather than the behavior of the consumers buying them. We categorize all products that are bought frequently enough as male, female or ungendered based on how often they are bought by women. The following graphs show distribution of female purchase share for UPCs bought at least 50 times in a half-year. The extra mass at the tails of the distribution indicates goods that are only ever bought by a single gender. When we restrict to just health and beauty products, we can see this finding is even more pronounced and skewed towards women. These graphs suggest that the product space for household goods is very gendered. Finally, we show that products bought almost exclusively by women are more expensive than comparable ungendered products or products bought exclusively by men. For each “decile” of female purchase share, we plot the average difference in log(Price) from comparable goods that are ungendered (goods that are bought equally by both men and women). We do this for the full sample of products (circular dots) as well as for markets where we may expect different amounts of gendering: health and beauty, alcohol, and produce (diamonds, squares, and triangles). For the full sample, we can see that, on average, products bought by women are priced higher than products bought equally by both genders or products bought more by men. This finding is particularly significant for health and beauty products, where products bought by women are priced on average 40% higher than comparable ungendered products. Interestingly, although we document the existence of products designed and bought exclusively for men, we do not see the same pattern of increased pricing. This descriptive evidence highlights stark differences in both the types of products and prices paid by men and women; these differences likely have implications for objects of concern like inflation, price indices, and welfare. The first step towards understanding the welfare impacts of these consumption inequalities is to identify and distinguish between the underlying economic mechanisms that may give rise to them. Is this a price discrimination story where women have more inelastic demand and thus can be charged higher prices? Or is this a story of men and women having different preferences where the goods that women prefer exhibit higher marginal costs? If this is a preferences story, why do men and women have such different preferences? We tackle these questions by modeling demand in the aggregate. Why are women’s goods more expensive? To attribute observed price differences to specific mechanisms, we model demand and supply and estimate the overall markups on individual UPCs underpinned by gender differences in substitution elasticities and differences in competitiveness between men's and women's consumer goods markets. Our aggregate analysis documents the extent to which price differences may be explained by price discrimination versus other factors. Our CES-demand framework corresponds with the estimating equation: where sm represents the elasticity of substitution of men and sf represents the elasticity of substitution for women. The subscripts can be interpreted as follows: i indicates a unique UPC, m denotes product module, g denotes gender, r denotes retail chain, l denotes county, and t denotes time which we measure in half-years. lmgrlt is a fixed effect for the module, gender, retail chain, location and time. The coefficient that we are explicitly interested in is (sm-sf), the difference in elasticity of substitution between men and women. We find that women are generally more elastic than men are by about 15%, which falls in line with our descriptive findings about price shopping behavior. This result is consistent across almost all departments in our data and is particularly strong in health and beauty, where women are more elastic than men are by about 30%. In our setting, price elasticity is a simple function of the elasticity of substitution and market share: ed = -s + (s-1)*h, where s is elasticity of substitution and h is the market share of the product. This means that women can still have more inelastic demand if competition over women’s goods is less than that over men’s goods. Below, we plot the log market share of products bought by men vs. bought by women. The strict left-shift of the women’s upc market share distribution relative to that of men demonstrates that the goods bought by women tend to be purchased in more competitive environments. Overall, we find that markets for women’s goods are generally more competitive than markets for men’s goods. This, combined with women having higher levels of elasticity of substitution indicate that women in general have more elastic demand. These findings imply that the Pink Tax that we observe in the data is not a story about price discrimination, but rather a story about preferences where the goods that women consume tend to cost more to produce. Women facing higher prices while having more elastic demand implies that, under some assumptions on market structure, average price differences between women’s goods and men’s goods are attributable to differences in the marginal costs of goods. Under oligopolistic competition, firms set their markups according to the Lerner rule, which yields this result. The next steps for this project will explore why men and women have different preferences and why women’s goods have higher marginal costs. Possible implications for welfare and policy In summary, our work demonstrates a sizable difference in prices paid by men and women for similar goods in line with depictions of the Pink Tax in popular media. This price difference induces further distortions to the gender wage gap as we presently understand. The standard consumption bundle for women is more expensive than that of men, so, in the absence of utility differences between their respective consumption bundles, women face lower purchasing power, compounding existing wage inequalities between men and women. We rule out the possibility that the observed difference in prices originates from differences in competition or demand characteristics, meaning that---on average---the Pink Tax is attributable to differences in production costs. There are several caveats to these findings: our analysis requires a high number of purchases of a product in our data in order to confidently assign the product a gender, this means that certain niche markets and products are left out of our analysis. This work has also not deeply engaged with why costs of producing women's goods are higher on average: our ongoing research here seeks to explore this channel, including gender differences in quality-taste and other behavioral-economic factors at play such as differences in consideration sets and inaccurate beliefs on product quality. Finally, our findings come with implications for public policy. In the 1990's and early 2000's, several US states in the 1990's ratified anti-price-discrimination laws along gender lines for the provision of services such as dry-cleaning and hair care at beauty salons. Recently, there has been a resurgence of legislation intended to counteract the Pink Tax for consumer goods, and understanding what drives the Pink Tax is imperative for these policies' success. For example, New York has recently passed into law a ban on gender differential pricing. The language surrounding this law clearly frames the Pink Tax as a price discrimination story with the underlying assumption that markups are higher for women’s products. Our findings would suggest that this may not be a welfare-enhancing policy because markups for women are already lower than those for men. To the extent that the Pink Tax is attributable to differences in production costs of goods, policy that aims to eliminate the Pink Tax by legislating prices may end up inducing market exit of goods producers. Moving forward, our future research will help inform policy to make consumption across the gender spectrum more equitable.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed